“She squeezes my hands very tight, and I squeeze back”

In this edition of the Weekender: a philosophy of dance, the joy of private notebooks, and summer jobs

This week, we’re dancing our way into philosophy, taking a summer job, reading private notebooks, and visiting grandma.

MEMOIR

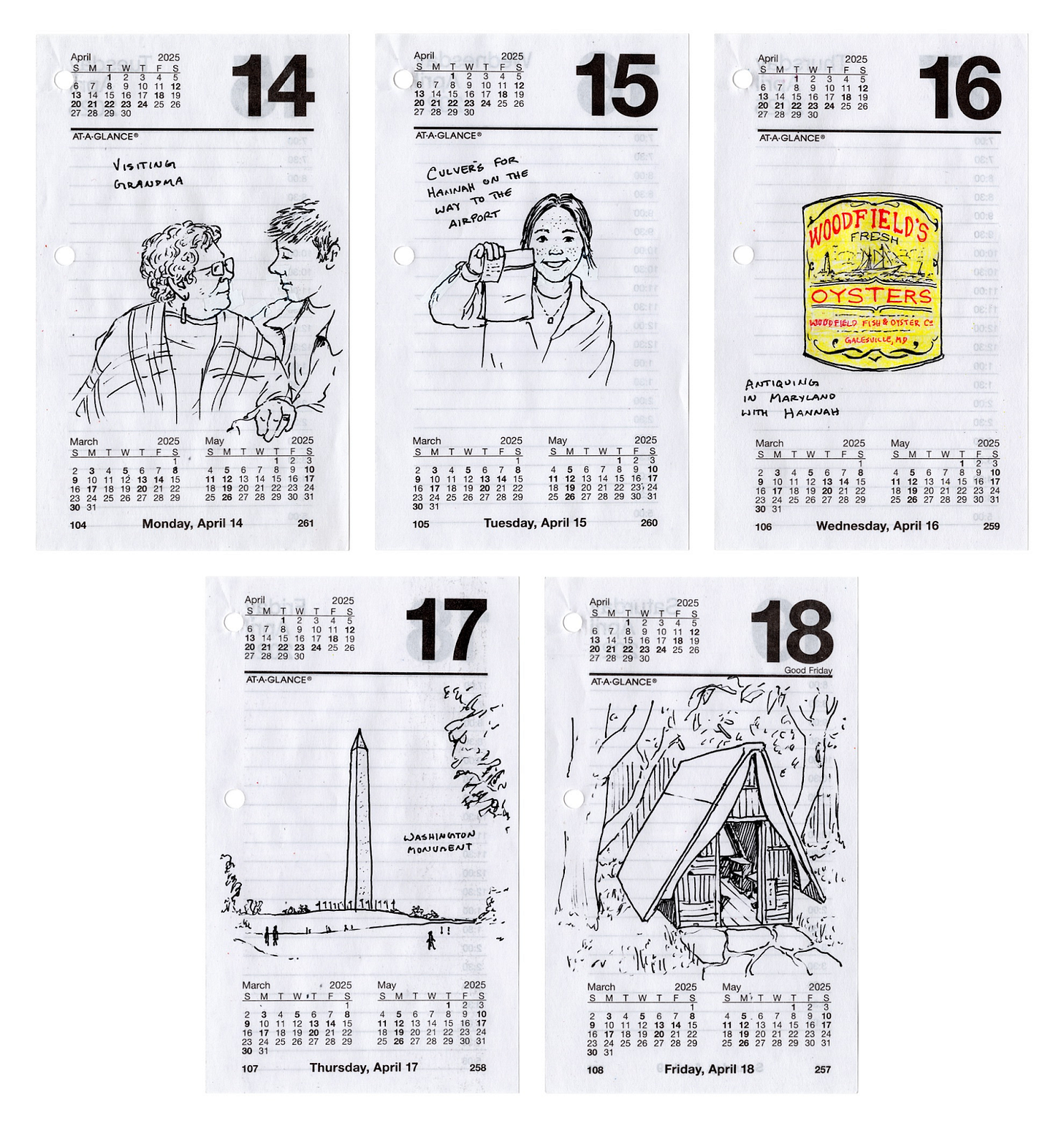

Artist’s diary

Chris Schwaar’s Substack shares an illustrated calendar of moments from his daily life. In this entry, Chris visits his grandmother—where perfume, earrings, and a shared squeeze of the hand say more than words.

Daily drawings: Week 16 of 52

—

inMy grandmother is wearing a beige plaid shawl and turquoise earrings that match her shirt. The earrings always match the outfit. The perfume always picked thoughtfully from the hundreds of bottles on her dresser. The stickers that seal the birthday cards painstakingly chosen.

My grandmother, who now rarely leaves the house, who plans her trips up and down the stairs with care, takes advantage of the details she still has choice over. The jewelry. The color of her nails. The flowers she has my mother plant in the garden.

I was not close with my grandma growing up. Even though we only lived an hour away, we rarely saw my grandparents more than three or four times a year. Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, perhaps a day in the summer when the lawn had been cut and the frogs were loud.

It wasn’t until all my older siblings left for college, and my grandma was unable to keep up the garden, that my mother started visiting once a week. My grandparents started to soften with age, and I began appreciating them more, as I grew older too. I’d tag along on visits with my mom. My grandpa, usually brash and aloof, started asking me about my art, quizzing me on jazz musicians. My grandma, her dogs now gone, watched nature shows on TV or gazed out of the bay windows, looking at the birds.

Her favorite bird is the Baltimore Oriole. I drew one for her a couple years ago and she hung it proudly in the living room. A small glass Ruby Throated Hummingbird, her second favorite, hangs from the light above the kitchen table. This is where she is usually sitting.

When we arrive, walking through the door from the garage, she looks over from the table, and in her high creaky voice, says “Hi honey, how are you?” She sounds tired. Her wrinkled hands are on the table, one placed on top of the other. I walk over and hug her, then crouch down, grab her hands, and say “What up, girl? How are you doing?” She grins down at me in her beige shawl and says “Oh I’m fine.” This is how it goes. The earrings perfectly chosen, the perfume just right for the day.

She squeezes my hands very tight, and I squeeze back, wishing I’d held her hands more often. But at least I’m holding them now.

DRAWING

LITERATURE

A peek behind the page

Henrik Karlsson’s meditation on private notebooks considers the thrilling intimacy of unvarnished thoughts.

On the pleasure of reading private notebooks

—

inA surprising number of my favorite books were not meant to be published. They were private notebooks, or fragments from works-in-progress that never got finished: among them Pascal’s Pensées, Simone Weil’s private essays, Lichtenberg’s Waste Books, Herzog’s Conquest of the Useless, Kafka’s diary, Joubert’s Carnets, Wittgenstein’s Blue and Brown Books, and Sei Shōnagon’s Pillow Book.

One reason I like this genre is that people censor themselves less when they are writing in private. I don’t mean that they are saying things that would get them ostracized in print (though that happens). I mean uncensored more generally: they allow their mind to be as it is on the page, however odd their thoughts are and however random the connections between them. They are not second-guessing if their thoughts are interesting to others, or trying to frame them in a certain way.

And, paradoxically enough, this is more interesting to read. Lichtenberg wrote a note about this in his private Waste Book (posthumously published 1800–06):

“An alert thinker will often find more that is instructive and delightful in the playful writings of great men than in their serious works. The formal, conventional, ceremonial is usually omitted from them; it is amazing how much wretched conventional stuff still appears in our way of narrating in print. Most writers put on airs, just like many people when they are having their portraits painted.”

For a more contemporary example of a similar phenomenon, Michael Nielsen says that the old bookmarking website del.icio.us had a “network” feature that

“(a) hardly anyone knew about; (b) let you follow other people; but (c) because no one knew, people just bookmarked unconsciously what they were really interested in. It was so much more interesting than Twitter etc…”

I think this is because our genuine thoughts (and interests) are more detailed and alive than the simulations we have of what we should say (or be interested in). When we think no one listens, we relax into the genuine. I’ve been told, repeatedly, that I hide my most interesting thoughts in the footnotes.

Browsing through private notes feels more like participating in a happening than reading a piece of literature: this is what happened, more or less in real time, inside another human. Their beauty has more in common with the beauty of nature than the beauty of art. It is sprawling, strange, tangled, and confusing—but the overall work has a deep structure to it that art can’t imitate. It is not the result of a plan but a generative process. I’m reminded of being in a pine forest, surrounded by large beings that stretch up from the ground.

PHOTOGRAPHY

SUMMER GIG

Working stiff

In The Republic of Letters, Wim Hylen recalls a uniquely challenging summer job at a butcher shop.

The Butcher’s Boy

—

inIn the summer between my junior and senior years of high school, I got my first part-time job. It was at the Colonial Village Meat Market, a butcher’s shop. I inherited it from a neighbor who had decided to quit and was looking for a replacement. He described it as an easy part-time gig. Sweeping up, stocking shelves, wiping counters: duties so easy that even I, who had not done a day of sustained physical labor in my life, could hack it.

Not much was expected of me at home other than to get good grades and stay out of trouble. But that summer my parents had strongly hinted that I needed to do something productive, preferably something that earned money, rather than hiding out in the basement listening to records, playing guitar badly, and brooding.

The owner of the meat market was an Italian guy who was probably in his mid-forties. He was short and not at all physically imposing. But he was intense and high-strung with dark eyes that seemed to bore through you. He scared the shit out of me. But to be fair, nearly everything scared the shit out of me in those days. I was chronically shy, deeply self-conscious, impossibly skinny, and looked much younger than my age. The world frightened me.

Many of the details of what I did at the butcher shop are sketchy. Anxiety affects memory and I was anxious nearly all the time. It was as if I was going through life holding my breath and averting my eyes, hoping that whatever was happening would quickly pass.

This is what I remember. The job entailed coming into the store near closing time and cleaning up. There was broom pushing and mopping involved but also some heavy lifting. I remember lugging 50 lb. bags of something (sawdust, maybe?) to a small storage space and crawling in there to make sure the bags were neatly arranged on top of each other.

I was shown the ropes by Sean, another high school student who worked there. He was a red-haired, adolescent version of the owner: short, intense, high-energy. He was going places and had plans for the future, which involved working hard and making plenty of money. He was everything I wasn’t.

My main task was to dismantle the upright butcher’s saw, clean out the hunks of meat and gristle that clung to the blades, and then reassemble it. Sean did his best to train me. He patiently demonstrated how to remove each part of the saw, scrape off the meat, disinfect the blades, and then put everything back together. He would walk through the steps while I watched and nodded as if I understood. But I didn’t understand. To me, the saw resembled an impossibly difficult jigsaw puzzle. So when I tried doing it myself (under Sean’s supervision), it was pure trial and error. I was merely guessing as to how the parts fit together. Back then I was only vaguely aware of my problem with spatial relationships, which would become glaringly and painfully obvious as I grew older. A college friend once described me as someone who would try to shove a dollar bill into the coin slot of a pay phone. To this day I am unable to properly wrap a birthday present. I can’t attach a luggage tag to my bags or tie a balloon, never mind put together IKEA furniture. My success rate in screwing in lightbulbs is about 50 percent. Reader, I once attempted to cook beans in a sieve. I am the anti-handyman. Although I can laugh about it now, my deficiencies remain baffling and frustrating and can still embarrass me when exposed.

Did I ever succeed in putting the butcher’s saw together correctly? I’m not sure. Maybe I did once or twice. But one day I came in to work to find the owner waiting for me. He led me over to the saw and told me he wanted to show me something. When he turned it on, the sound it emitted was a deafening screech of metal grinding on metal. He glared at me and let me soak in what my incompetence had wrought. He was angry, of course, but the prevailing theme of the ensuing lecture was disappointment that Sean had not trained me properly. In his mind, that could be the only explanation. It may be a false memory but my recollection is that in my own meek way, I stuck up for Sean and insisted that I had been trained well and that the screwup was my own fault. I sure as hell hope I said something like that.

POETRY

MUSIC

DANCE

Body in motion

Drawing on Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of embodied perception, Vincent Jenewein’s essay explores how we move through the world—through music, dance, and the rhythms that shape our experience.

My body is a melody

—

in Infinite SpeedsWe always form certain predictions and expectations about the music’s future trajectory. If a pattern keeps repeating, I attune myself to its continuance; when there is a change or shift, I adjust my horizon of anticipation accordingly. In general, human beings are quite good at anticipating the trajectory of rhythmic and tonal patterns. When a drummer plays a repeating rhythmic pattern, we are able to roughly anticipate where the pattern’s hits will fall, we know where the kick will land, we know where the snare will land, and so on—without this capacity, it would be impossible to ever get into the groove of any music.

And yet a key part of what makes music perceptually engaging to us is also the fact that there is often some kind of discrepancy between what we anticipate and what comes to happen. A drummer’s playing will never be perfect; every hit will be off just slightly from where it “should be”, not far enough to really consciously register as being off-beat, but enough for our body to take note, which is much more sensitive to such subtle variations than the ear.

Similar phenomena of perceptual nuance also exist with respect to parameters like pitch, volume and timbre, and we enjoy such variations precisely because they play with our sense of anticipation—a “funky” drummer is one who responds to our anticipations, while also leaving enough space for variation and nuance. When a DJ brings in a new track that changes up the rhythmic flow of a set, the crowd will respond through the surplus of expressiveness that is the movement of their bodies, in turn prompting a response from the DJ, forming a reciprocal expressive dialogue.

While the human body’s general capacity to respond to nuance is innate, clearly not everyone is able to always perceive the same degree of nuance. A trained pianist will be able to hear nuances in the tone of different pianos that will sound identical to a layperson, but may be unable to hear similar nuances in other instruments. Such personal habituations are of course also shaped by cultural and historical factors. When talking about the perception of color, Merleau-Ponty is keen to point out that the way we perceive a color like red is inherently interwoven with a rich tapestry of cultural and historical associations—nobody can objectively perceive red “as it is” because we always encounter it within a pre-existing world of colors full of cultural and historical significations.

Is this not also true in the case of music? Non-Western traditions centered around microtonal scales often sound alien and unnerving to Western ears, while they sound perfectly natural to people who have grown up within that tradition. Such affinities and dissonances for certain sounds and tunings have been ingrained into us from early childhood through cultural osmosis; not as an intellectual dogma, but as bodily habits and attitudes, certain ways of moving and perceiving that have become institutionalised. Culture is a bodily institution.

ART

FOOD

What we’re watching this week

Monday, June 2, at 9 p.m. ET

will be going live with to discuss Pride, dating, and sex tips.Tuesday, June 3, at 5 p.m. ET

Join

for a live conversation with primary care doctor and medical writer to discuss who to trust in medicine and public health, how to navigate medical news, and the role of primary care doctors in health care.Substackers featured in this edition

Art & Photography:

, , ,Video & Audio:

,Writing:

, , , ,Recently launched

Inspired by the writers featured in the Weekender? Creating your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

I would love more of articles from writers like Chris Schwaar. Lovely write up. She squeezes my hand and I squeezed mine back. 👏👏 Beautiful.

Enjoy the time and keep holding her hand. My grandmother passed away almost 30 years ago. I still miss her.