“We don’t know why we do or don’t like someone. We just feel it.”

In this edition of the Weekender: the Zynnification of culture, Andy Warhol’s cookbook, and the algorithm of attraction

This week, we’re listening to the Beach Boys, categorizing folktales, analyzing attraction, and reading a cookbook for people who don’t cook.

IN MEMORIAM

Remembering Brian Wilson

It’s been a tough week for music fans. In this post, Mark McInerney extolls the chamber-pop brilliance of Brian Wilson.

Postwar Dreams, Pop Symphonies, and the Genius of Brian Wilson

—

inOne of my earliest memories is listening to the Beach Boys.

For my father, they weren’t just a band—they were a time machine. He was part of that postwar wave that caught the California dream at full tide. He surfed. He lifeguarded at Jones Beach. And when the Beach Boys hit the airwaves, it felt like the soundtrack had finally caught up to real life—sun, speed, salt, and youth in eternal bloom.

At first, it was all joyrides and jukeboxes—Surfin’ U.S.A., Little Deuce Coupe, the thrill of American adolescence. But as the ’60s deepened and the skies darkened, so did the songs. And at the center of it all was Brian Wilson.

Today, we learned that Brian has passed, at 82.

So: Brian Wilson is gone. Another architect of American music. Another side of the coin—Sly Stone, too, just earlier this week.

And it’s worth pausing here—because genius is a word we toss around too easily. But Brian Wilson was a genius. If he’d been born in the 1700s, he’d have been writing court music for kings. Instead, he gave his symphonies to the surf, and his psalms to the suburbs.

He fused Chuck Berry with Bach, barbershop with Baroque, crafting pop that could stand beside anything in the Western canon. Pet Sounds wasn’t just a turning point for the Beach Boys—it was a turning point for music itself. Paul McCartney, who famously saw Brian as his only true rival, once called God Only Knows “the greatest song ever written.” When he heard Pet Sounds, he saw the future—and responded with Sgt. Pepper.

Ten years ago, I saw Brian perform Pet Sounds at the Beacon Theatre in New York. It was transcendent. The closest thing I’ve ever witnessed to chamber music in pop. There he was—fragile but radiant—surrounded by an extraordinary band, playing music that had once nearly broken him. Now, he was lifted by it.

LAWBREAKER

Video shared by Mitch Santell

CULTURE

“Consider the pouch”

Ock Sportello explores the “Zynning of culture” in a post that swings from a notably swagless NBA to the ubiquity of safe, boring, mood-board fashion.

Toward a Unified Theory of Uncool

—

inI am wont to ascribe outsize importance to the nicotine delivery system du jour. Perhaps there is no significant cultural or political dimension to how, at any given moment, people get a buzz. Yet I can’t help but feel subjected, over the past few months, to an all-out assault of writing about Zyn. I have read, in Max Read’s instantly canonical terms, how shared Zyn addiction has come to group together the lamest young men on the internet. I have learned, per Carrie Battan’s incisive reporting, the irony of these attempts to code Zyn use as masculine. I have read about young men banding together on Reddit to quit Zyn. I have read these Reddit threads myself, because I have toyed with talking myself into these apparently harmless pouches to ease the moments during which life without nicotine starts to drag; I have come so far, at times, as to convince myself that the only thing to worry about with these pillows of nicotine salt are their aura, rather than health, ramifications. I have talked to friends who appear to be in Zyn’s vise grip—friends who would not be caught dead with the sort of people who tweet about dating in New York City from burner accounts. Zyn is in. Neither the perceived political or the real public health ramifications of this fact concern me. All I care about, for purposes of this blog, is what it means for the vibe.

Calling Zyn pouches “uncool” is a misdiagnosis not just of magnitudes but of kind. Zyn’s early American adopters were surely uncool, but the product itself is noteworthy precisely for its nothingness. In a moment where Instagram starter-pack brain has convinced young phone users, consciously or otherwise, that they and the people around them are the sum of the objects they carry with or on them, Zyn stands as perhaps the first negative staple. Ignore, momentarily, the hockey-puck-shaped container, the outline of which protruding through your pants immediately reduces you in my mind’s eye to one of my high-school-age cousins at Thanksgiving dinner. Consider the pouch.

Cigarettes are, regrettably, sexy. The twist of smoke, the alternately sleek and threatening phallus . . . let’s not belabor it. That cigarettes look cool is a sort of universal truth; if it eludes you, it won’t after two drinks. Vapes, in their assortment of shapes, sizes, colors, and flavorings, occupy a sort of spectrum of goofy, but goofy’s fine. Goofy, crucially, is something. The Zyn, once tossed into the mouth, disappears. There is no spit, no observable difference in the user, no activity. Literally nothing occurs. The Zyn is a sort of invisible IV drip eliciting in its users a functionally negligible buzz. From the standpoint both of experience and presentation, Zyn use ought form no closer fraternity among its users than their shared status as people who breathe air would.

Zyn is safe, if not in the FDA-approved sense. Virtually undetectable and in all likelihood healthier than other nicotine-delivery mechanisms (I don’t like talking about things so transactionally, but this warrants an exception), they transform an ostensible vice into an addiction divorced from its attendant risk. They represent a sea change: a nearly ubiquitous product that people expect, on some level, to be cool, but which by virtue of its safety—defined, of course, by its essential lack—ends up a sort of disturbing nothing. They remind me, in other words, of the current cohort of budding NBA superstars.

ANIMATION

TECH TALES

Folktales and file systems

In the Aarne-Thompson-Uther folktale taxonomy, stories are grouped by plot and motif: “For instance, Type 311 is Rescued by the Sister. Type 325 is The Magician and His Pupil. There are also types of fable that can be classified with others that tell of The Maiden Without Hands (706), The Girl as Wolf (409), and The Girl as Flower (407).” Here, Sheila Heti considers a category that has jumped from myth to reality in the modern era.

The Spirit in the Blue Light

—

inLately, I have been thinking a lot about Type 562, The Spirit in the Blue Light, since I spend most of the day captivated by a spirit in a blue light: my computer. Often when I’m feeling muddled, I go to my computer and clean up my files, or classify miscellaneous documents, or trash things, feeling a bit like I imagine Aarne, Thompson and Uther felt as they tried to bring order to the orderless jumble that lay before them. In my case, it is not a history of folk storytelling but years of thinking, shopping, corresponding, bill-paying, news-reading, and idle fantasizing, as though my computer really is my mind, externalized, or an apartment which needs cleaning, or contains all the stories that have ever been told. It’s as if the spirit in the blue light of my computer and the spirit inside me at some point joined hands, and my eternal spirit is now more comfortable when it is joined with the spirit of this digital blue light, than it ever again will be—alone or apart from it.

I wondered at one point whether the narrative of a Spirit in the Blue Light fable could give me some insight into what increasingly felt like an essential relationship, or an extension of myself, or this need I had to be with my computer almost continuously throughout the day. Here is what I read:

A wounded and wandering soldier encounters a witch in a forest. He asks her if she could provide him with lodging. She agrees to put him up if he’ll help around the house. For two days he helps her, and for two nights he sleeps. On the third day, the witch asks him to fetch her the blue light that is shining at the bottom of her empty well. When the soldier climbs down and reaches the bottom, he realizes he is trapped there. To calm himself—and to think more clearly about his situation—he decides to have a smoke. He notices a matchbox lying on the ground, a blue light glinting off from one of its sharp corners. Striking the match, he lights his pipe. Suddenly, a spirit emerges in the smoke of the blue flame! This spirit tells the soldier that he will grant him three wishes. First, the soldier asks that the witch be killed. She is, and the soldier climbs from the well and runs free. Then the soldier asks to have brought to him the princess of the land, to serve as his maid. The princess is brought and begins sweeping up, doing the chores that the soldier had been doing. The king, furious at learning that a lowly soldier is using his daughter in this way, has him captured. Right before the soldier is executed in the centre of the town square, the soldier asks if he might have a final smoke. His request is granted, and he lights his pipe with the match from the witch’s matchbox, and the blue spirit reappears! The soldier asks it to kill all the citizens in the square, giddy with the anticipation of witnessing his hanging, and the spirit kills them all. Fearing for his life, the king surrenders himself, and gives the soldier his entire kingdom, and his daughter as a bride.

At first glance, it is not clear that this story has anything to say about my relationship with my computer.

In the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index, the Spirit in the Blue Light fables fall within the category Magical Object Provides a Supernatural Helper. This is a sub-class of Tales of Magic stories. (There are only six other main classes of story: Animal Tales, Religious Tales, Realistic Tales, Formula Tales, Tales of the Stupid Ogre, and Anecdotes and Jokes.)

My computer, then, is not an animal, not something realistic, not a stupid ogre—but a magical object, and the applications within it—Word, Gmail, Excel—are supernatural helpers. I guess it is something of a supernatural helper who can connect you with friends across the world or disappear three hundred of your dollars on a red dress that seems perfect and soon arrives at your door but doesn’t fit you at all. I guess it is a supernatural helper that can give you glimpses into the sufferings of humans hundreds of thousands of miles away. I guess it is a supernatural helper that can write your college essay on Robespierre, or a difficult letter to an unfaithful husband, finally asking for a divorce.

SECURITY

ROMANCE

Just my type

Ever-smarter dating algorithms promise finer and finer levers to optimize for attraction. But as Rachel Cohn writes, there’s a problem: no one really knows why we like who we like in the first place.

The Dating App Revolution Is Coming

—

inI’d like to think I have some unique insight into just how difficult it is for people to verbalize what features attract them to someone, thanks to the interviews I’ve done for this newsletter. Every single person that I have interviewed—really every single one—has struggled to articulate or rationalize why they do or don’t like someone. If I have learned nothing else over the last 6 months, it is that romantic attraction often defies human language.

When I consider again the scenario I faced in 2023, wondering why I wasn’t meeting people I liked as much as the non-monogamous man I met at the party, I’m not sure what I could have told the algorithm that would have been useful.

I’d like to be shown more profiles of people who are curious about the world and possess an immediate warmth? Can an algorithm reliably detect those things from a profile? Can I???

It’s possible that kind of prompting could be useful. Or that there are proxies for those qualities that are detectable that I could prompt for to turn up more of the kind of person I’m seeking. Like maybe educational background could be an ok proxy for curiosity? And a big smile could be a proxy for warmth?

But on some level, I have a sinking suspicion that there is very little I or any user could reliably point to that would help an algorithm find better profiles for us. (The one exception I can think of is physical attributes, but even there I’m not sure we should want Hinge to be responsive to what I fear will be all kinds of terrible bias and discrimination.) All the traits that I know are most important to me seem too unspecified, too subjective: kindness, humility, playfulness, open-mindedness.

And anything too specific feels like it runs the risk of misdirecting the algorithm or narrowing in on arbitrary and ultimately superficial features.

With the guy from the party, for example, I could explain what his research was and what he did for fun in his downtime and the kind of jokes he laughed at, and the way he held his fork at the restaurant. But none of that explains why I liked him. It was his aura, his essence, the vibe.

Unfortunately for Hinge, I suspect that this is often the case. We don’t know why we do or don’t like someone. We just feel it. And what can an algorithm do with that?

PHOTOGRAPHY

COOKBOOKS

The art of dinner

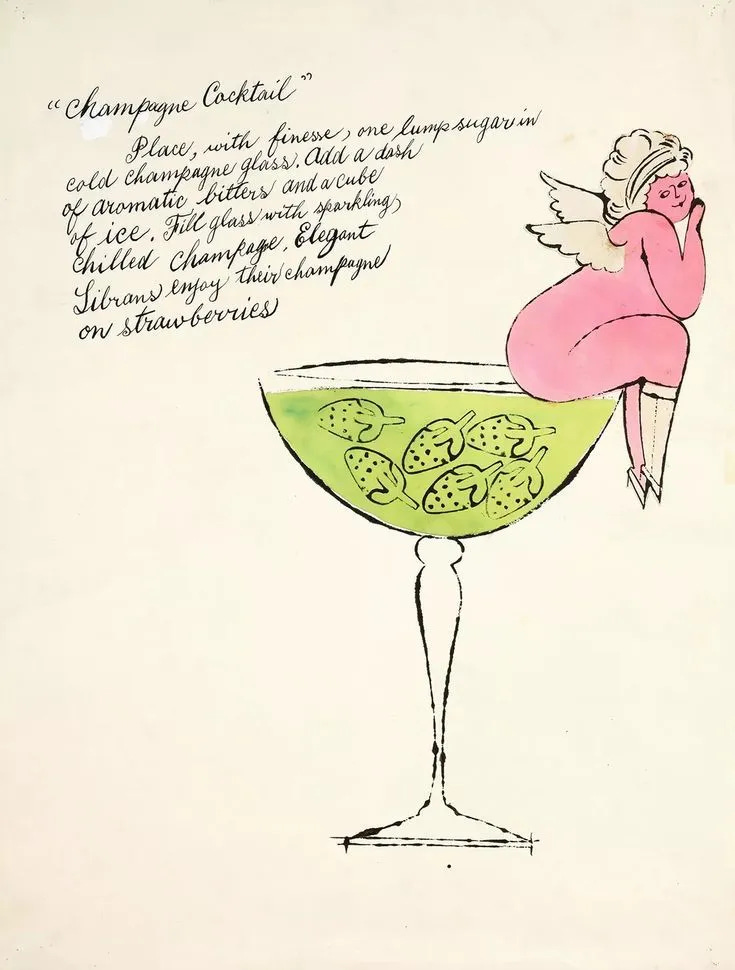

Before Andy Warhol was Andy Warhol, he collaborated on a delightfully nonsensical cookbook for people who don’t cook.

For Hosts Who Don’t Cook

—

inCan’t cook but love to entertain? Then Wild Raspberries is for you. It’s a completely ridiculous cookbook I turn to again and again. Not for the recipes; they are basically nonsense, and I don’t cook anyway. I turn to it for inspiration. For the feeling.

Wild Raspberries manages to be whimsical (always essential), humorous, laid-back, and a little traditional, without being stuffy. It reads like a child’s take on adult sophistication, complete with plenty of misspelled words. A blueprint for “playing adult.” And honestly, aren’t we all just doing that anyway?

The book was a collaboration between Andy Warhol (before he was famous), who did the drawings, his friend Suzie Frankfurt, an interior decorator who wrote the recipes, and Andy’s mother, Julia Warhola, who did the calligraphy. It was 1959. Warhol was still working as a commercial illustrator, and the three of them imagined the book would sell like crazy. It did not. They self-published a small run and gave it to friends and clients. Originals now sell for over $50,000.

The book was satire—a wink at the overly earnest French cookbooks of the era, with their meticulous directions and intimidating sauces. Suzie wanted to be the ultimate hostess, like her mother, but couldn’t quite stomach the seriousness of it all. So she turned her ambivalence into humor.

“We had to write a funny cookbook for people who don’t cook. My mother, who was a hostess sine qua non, deemed the most important thing for a new bride was to be a good hostess. I wanted to emulate my mother, of course, and it was the year all these French cookbooks came out. I tried to make sense of them. ‘Make a béchamel sauce,’ they’d say. I didn’t even know what that was.”

The drawings are loose and cartoonish, full of delightful details—chubby cupids perched on champagne coupes, a pig in a bow. The colors are bright and irreverent, the lines carefree. It’s the imperfections that give it life. Nobody involved took themselves too seriously, and therein lies the charm.

The recipes are full of self-deprecating wit. Like the Chocolate Balls a la Chambord, which are only served with no-cal ginger ale to “very thin people.” Or the Omelet Greta Garbo, which is “always to be eaten alone in a candlelit room.” The cooking tips are anything but practical. A favorite of mine is for the Seared Roebuck: “It is important to note that roebuck shot in ambush is infinitely better than roebuck killed after a chase. Keep this in mind on your next hunting trip.” Or “Gefilte of Fighting Fish,” which instructs the chef to “immerse them in sea water and allow them to do battle until they completely bone each other.”

And then there is this gem. The full recipe for Piglet:

“Contact Trader Vic’s and order a 40 pound suckling pig to serve 15. Have Hanley take the carey cadillac to the side entrance and receive the pig at exactly 6:45. Rush home immediately and place on the open spit for 50 minutes. Remove and garnish with fresh crabapples.”

COLLAGE

What we’re watching this week

Monday, June 16, at 9 p.m. ET

of Messy Mondays will go live with of to discuss sex, therapy, and performance anxiety.Tuesday, June 17, at 5 p.m. ET

of will go live with Rachel Rubin, MD, a urologist and sex medicine expert, to discuss hormones, libido, and the life-saving role of vaginal estrogen.Friday, June 20, at 10 a.m. ET

will lead an Inner Sun meditation to celebrate the summer solstice that will focus on healing the nervous system and developing clearer thinking and connections.Friday, June 20, at 7 p.m. ET

of and of will go live to discuss how to style your home.Substackers featured in this edition

Art & Photography:

, ,Video & Audio:

,Writing:

, , , , ,Recently launched

Inspired by the writers and creators featured in the Weekender? Starting your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

Our energies are either aligned or misaligned with people. This is why we can just sense if a person connects well with us or not. The older we get, the more refined our energetic receptors get…we can call this your intuition. This is why we have to trust our intuition, it is customized for us and our highest good.

We tend to over think things when it comes to people when far too often our gut instinct is what we need to listen to, if some one isn’t good for you in one way or another your gut will let you know.