“There’s no replacement for text, and there never will be”

In this edition of the Weekender: anti-dystopian TV, experimental poetry, and the enduring power of the written word

This week, we’re discussing poetry with our hairdressers, betting on Best Picture, and defending the written word.

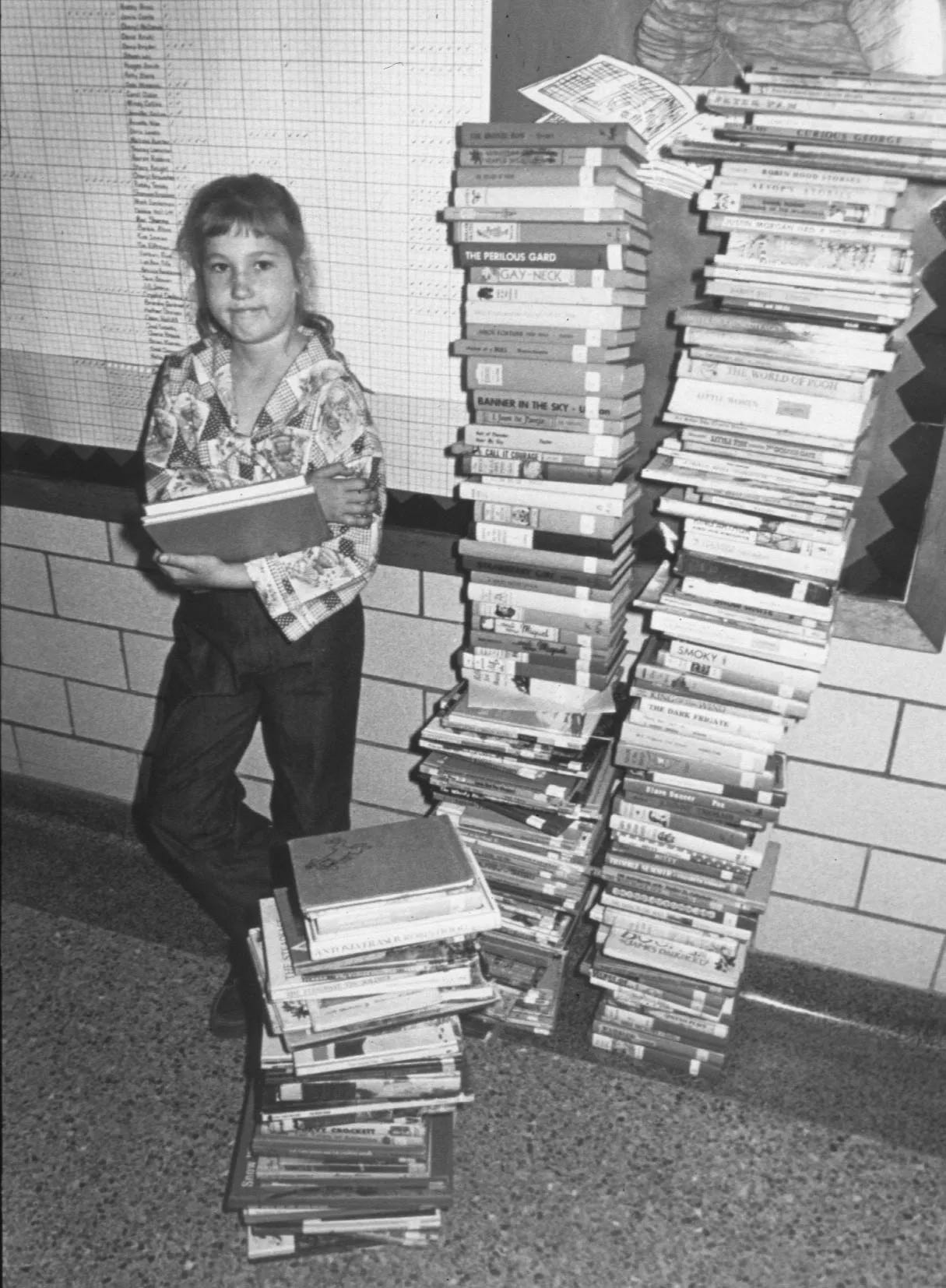

THE WRITTEN WORD

The power of text

In which Adam Mastroianni counters the familiar narrative that reading is dead, arguing that the written word commands a power no TikTok can possess.

Text is king

—Adam Mastroianni in Experimental History

Perhaps there are frontiers of digital addiction we have yet to reach. Maybe one day we’ll all have Neuralinks that beam Instagram Reels directly into our primary visual cortex, and then reading will really be toast.

Maybe. But it has proven very difficult to artificially satisfy even the most basic human pleasures. Who wants a birthday cake made with aspartame? Who would rather have a tanning bed than a sunny day? Who prefers to watch bots play chess? You can view high-res images of the Mona Lisa anytime you want, and yet people will still pay to fly to Paris and shove through crowds just to get a glimpse of the real thing.

I think there is a deep truth here: human desires are complex and multidimensional, and this makes them both hard to quench and hard to hack. That tinge of discontent that haunts even the happiest people, that bottomless hunger for more even among plenty—those are evolutionary defense mechanisms. If we were easier to please, we wouldn’t have made it this far. We would have gorged ourselves to death as soon as we figured out how to cultivate sugarcane.

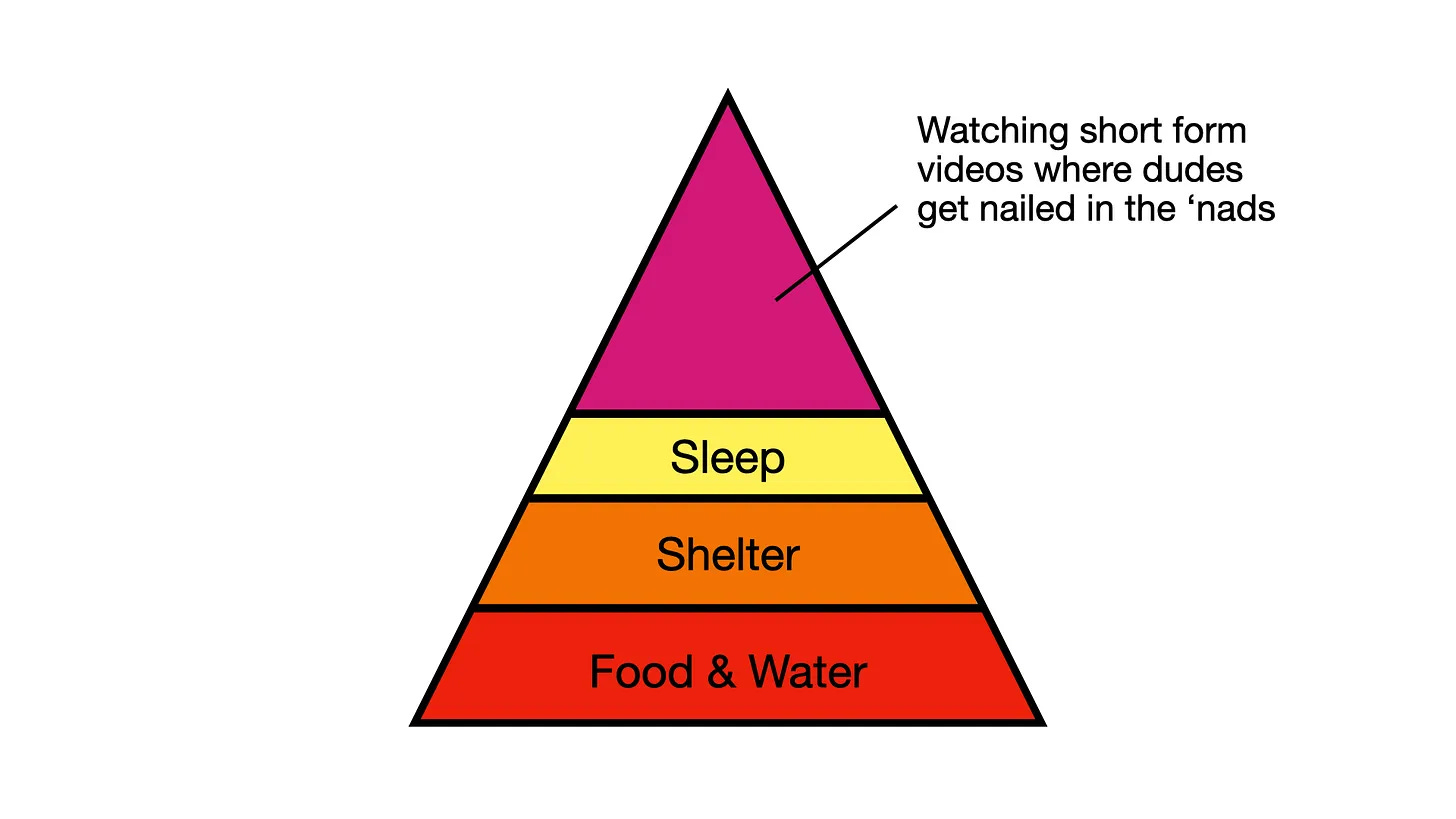

That’s why I doubt the core assumption of the “death of reading” hypothesis. The theory heavily implies that people who would once have been avid readers are now glassy-eyed doomscrollers because that is, in fact, what they always wanted to be. They never appreciated the life of the mind. They were just filling time with great works of literature until TikTok came along. The unspoken assumption is that most humans, other than a few rare intellectuals, have a hierarchy of needs that looks like this:

I don’t buy this. Everyone, even people without liberal arts degrees, knows the difference between the cheap pleasures and the deep pleasures. No one pats themselves on the back for spending an hour watching mukbang videos, no one touts their screentime like they’re setting a high score, and no one feels proud that their hand instinctively starts groping for their phone whenever there’s a lull in conversation.

Finishing a great nonfiction book feels like heaving a barbell off your chest. Finishing a great novel feels like leaving an entire nation behind. There are no replacements for these feelings. Videos can titillate, podcasts can inform, but there’s only one way to get that feeling of your brain folds stretching and your soul expanding, and it is to drag your eyes across text.

That’s actually where I agree with the worrywarts of the written word: all serious intellectual work happens on the page, and we shouldn’t pretend otherwise. If you want to contribute to the world of ideas, if you want to entertain and manipulate complex thoughts, you have to read and write.

According to one theory, that’s why writing originated: to pin facts in place. At first, those facts were things like “Hirin owes Mushin four bushels of wheat,” but once you realize that knowledge can be hardened and preserved by encoding it in little squiggles, you unlock a whole new realm of logic and reasoning.

That’s why there’s no replacement for text, and there never will be. Thoughts that can survive being written into words are on average truer than thoughts that never leave the mind. You know how you can find a leak in a tire by squirting dish soap on it and then looking for where the bubbles form? Writing is like squirting dish soap on an idea: it makes the holes obvious.

That doesn’t mean every piece of prose is wonderful, just that it can be. And when it reaches those heights, it commands a power that nothing else can possess.

I didn’t always believe this. I was persuaded on this point recently when I met an audio editor named Julia Barton, who was writing a book about the history of radio. I thought that was funny—shouldn’t the history of radio be told as a podcast?

No, she said, because in the long run, books are all that matter. Podcasts, films, and TikToks are good at attracting ears and eyes, but in the realm of ideas, they punch below their weight. Thoughts only stick around when you print them out and bind them in cardboard.

I think Barton’s thesis is right. At the center of every long-lived movement, you will always find a book. Every major religion has its holy text, of course, but there is also no communism without the Communist Manifesto, no environmentalism without Silent Spring, no American Revolution without Common Sense. This remains true even in our supposed post-literate meltdown—just look at Abundance, which inspired the creation of a congressional caucus. That happened not because of Abundance the Podcast or Abundance the 7-Part YouTube Series but because of Abundance the book.

A somewhat diminished readership can somewhat diminish the power of text in culture, but it’s a mistake to think that words only exercise influence over you when you behold those words firsthand. I’m reminded of Meryl Streep’s monologue in The Devil Wears Prada, when Anne Hathaway scoffs at two seemingly identical belts and Streep schools her:

...it’s sort of comical how you think that you’ve made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry when, in fact, you’re wearing a sweater that was selected for you by the people in this room.

What’s true in the world of fashion is also true in the world of ideas. Being ignorant of the forces shaping society does not exempt you from their influence—it places you at their mercy. This is easy to miss. It may seem like ignorance is always overpowering knowledge, that the people who kick things down are triumphing over the people who build things up. That’s because kicking down is fast and loud, while building up is slow and quiet. But that is precisely why the builders ultimately prevail. The kickers get bored and wander off, while the builders return and start again.

ANT ART

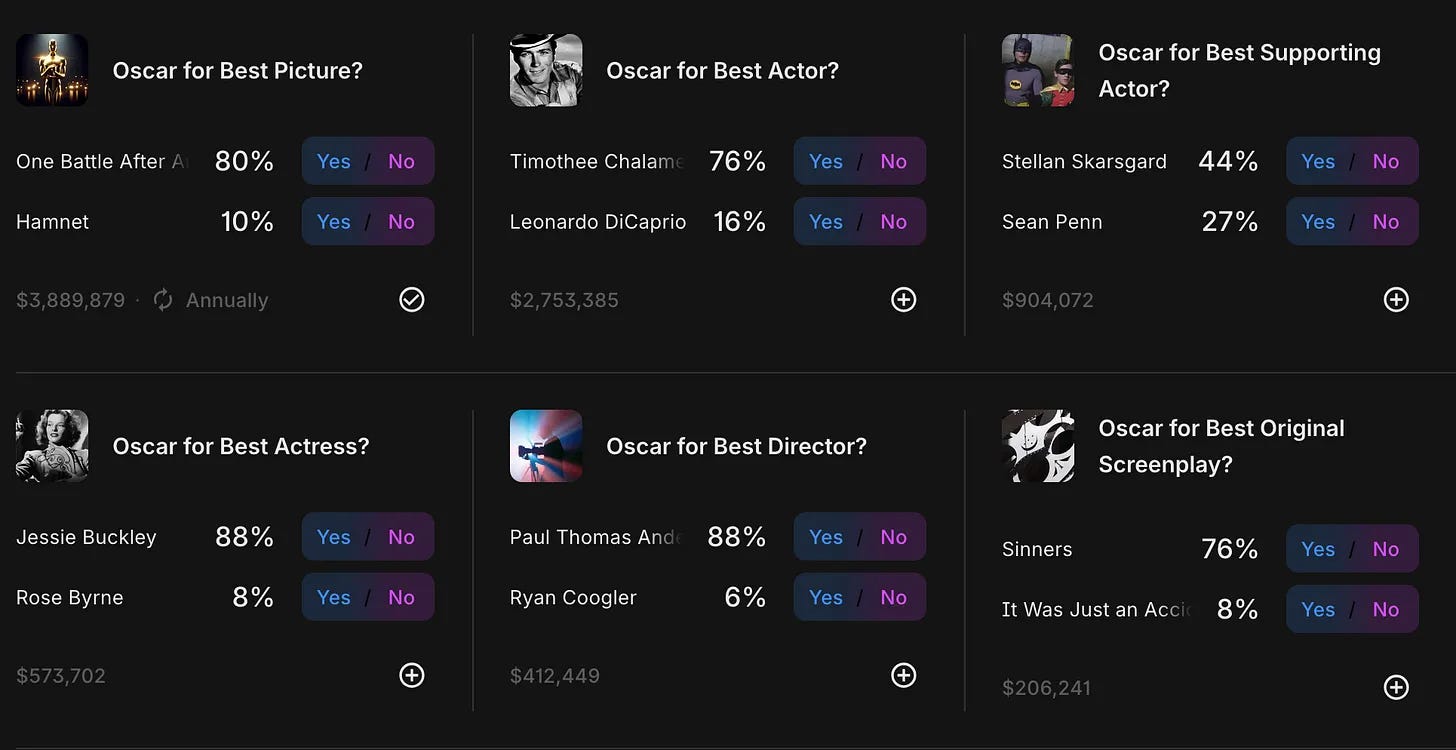

AWARDS SEASON

Betting on Best Picture

As prediction markets blur the line between gambling and forecasting, Andrew Truong interviews an Oscars betting expert on reading narratives, calculating odds, and turning a profit.

How to Win (or Lose) Money by Betting on the Oscars

—Andrew Truong in Buttered Popcorn

Thanks for chatting with me about the wild and wonderful world of betting on—sorry, predicting—the Oscars.

Predicting, yes. It is legal if it’s a prediction market. We’re not betting. We’re not gamblers here!

No, it is gambling, but in the way the stock market is gambling. I think the line conceptually and maybe morally is pretty blurry. And it’s really just about the regulatory structure. The way I think they justify it is they say, “We’re just a tool to aggregate information.”

When did you first get into Oscars betting?

I had gotten good at the usual Oscars pool, like when you go to an Oscars party and everyone makes their picks. Around 2018 it came up in conversation with a friend of a friend who runs an underground poker ring. That’s like his full-time job, he’s had [a certain former NBA star] show up to his games.

He was like, “Dude, if you’re actually good at predicting the Oscars, like let’s put some money down. I know a bookie.” It was just me picking what I think is going to win, and then him making sure the odds were worth betting on. We weren’t going to bet on anything where a film was an 80-90% favorite.

The first year we did this was for the ceremony in 2020. This was the Parasite year and I got super lucky. We did not bet on every category, but the ones we did, we got all of them right.

A lot of people heard us brag about it, so the next year, we got a big group together to put a lot of money down. And I do terribly, like really terribly. I got everything wrong except for Frances McDormand in Best Actress. But that won us all of our money back and we just broke even.

After that, I started getting more visibility into how the oddsmaking worked and would place flyer bets. We wouldn’t just bet on things that I thought were going to win but things that were mispriced.

And how did you do last year?

My group put down a total of $15,000 across 12 categories. Our adjusted odds were around 61% and we hit on 87%, so we outperformed our odds. We made about a 50% margin.

So your profit was $7,500.

Exactly. I just pick things and then people just pony up money. We’re a bit like a venture capital firm. I prepped a spreadsheet for every single category and wrote down my takes. Some people make their own bets on the side based on that.

What makes Oscars betting more appealing compared to sports?

Right now, you don’t have to be super sophisticated. You don’t need a mathematical model to have an edge. It’s about narrative, and that is a much harder thing to mathematically measure. You need to understand trends and tones.

Last year you switched from a traditional bookie to betting on Kalshi. What was the reason?

There were two reasons. One is that the odds were better for us. Kalshi is more volatile than underground betting, but that means more opportunity to be had.

And then, two, it was easier. We didn’t have to worry about pooling money together to clear a minimum bet with a bookie. That was a big thing. With Kalshi, we actually have the opposite problem. Once you start putting in enough money, you’re demonstrably changing the odds.

That was something I was looking at, the total market volume. Best Picture has almost $4 million in play, but International Feature only has around $30,000. If I put $1,000 into that category, it’s going to move the odds dramatically.

That’s actually why I’m not putting more money into International Feature. The amount I wanted to put in would have moved the odds to a point where I didn’t want to be in anymore. That didn’t happen with a bookie, where the lines were fixed. It doesn’t happen in sports betting either, because the volume is so high that no single bettor can really move the line.

It’s the opposite of the stock market. In the stock market, it’s better to have a big position because you can start to influence the company. Here, it doesn’t pay to be a big fish in a small market.

Unless you start holding Academy members hostage.

We don’t need to go into market manipulation. I’d encourage anyone who believes in a big Oscars-rigging conspiracy to do some research into how the voting and auditing actually work. I’m not a truther.

What’s your starting point with making your predictions?

I have a set of heuristics that I follow, a set of Oscars truths. One of my heuristics, and I think this is what people get wrong more than they get right, is that there’s usually a narrative for the night. These awards are not isolated events, there’s correlation. It’s Pennsylvania and Ohio in the presidential election. That being said, every category does exist on a spectrum. Something like Best Director is probably the best example of correlation with Best Picture.

But there are other categories—the technical ones more than others—where there isn’t a correlation. Sound is a great example of this. Does it matter how good the movie was? Not at all. Does it matter how good the sound was? A lot.

I think about Suicide Squad winning the Best Makeup Oscar. People were a little confused and I was like, “Well, they’re not awarding the best movie with makeup. It’s the best makeup in a movie.”

Great example. There’s a difference between predicting what Academy voters like and what they are going to judge as a better-crafted movie, especially in branch-specific categories. And that’s a core part of my philosophy, to watch the movies and separate the two.

Do you look up or calculate any stats, or are you mostly going on instinct?

Both. I’ve looked at the numbers over the last 10-15 years. Most of the time—and I think this is true even in sports—you want cases where the eye test matches the numbers. You don’t want to be led purely by the data, and you don’t want to be led purely by the eye test.

This is probably the hottest take of my heuristics: I don’t think the Oscars reward bad movies. There was an era where they were more likely to. But if you look at the Best Picture winners over the last 10 to 15 years, I’d actually be hard pressed to say any of them were bad. I’m not saying they pick the best movie every year, but they’re not picking something that’s poorly made. They have better taste than that.

I think that started around 2015, after Oscars So White. When they expanded the Academy and made it less of an old boys’ club, that’s when it started to correlate more with actual excellence. Who knew that by diversifying your voting population, you actually end up with better results, right?

PAINTING

POETRY

Of haircuts and poetry

Harriet Truscott on being asked about experimental poetry while getting an asymmetric haircut.

‘Fluff and puff’ at the T.S. Eliot Prize

—Harriet Truscott in The Little Review

Somehow I mentioned to my hairdresser that I was a poet, perhaps to justify my split ends, or my lack of plans for Friday night. My hairdresser told me that he cut the hair of ‘a poet, Mr Prynne’. Did I know Mr Prynne’s poetry?

I said I did.

My hairdresser asked me if I was ‘a poet like Mr Prynne’.

I said that Mr Prynne was a renowned and distinguished poet, and that I was not. That Mr Prynne had probably published about 50 books of poetry, and that I had not.

At this point my neck was strained backwards over the washbasin and my head was being sluiced with water.

I told the ceiling that in fact I had published zero books of poetry.

How many? said my hairdresser.

None, I said.

My head was thoroughly scrubbed now, and I was led back to the stylist’s chair. My hairdresser asked me to describe Mr Prynne’s poetry. I opened my mouth.

He asked me to keep my head straight, because my asymmetric cut risked becoming symmetric.

I said that Mr Prynne’s poetry was hard to describe.

It’s quite experimental, I said.

What does that mean? he asked me.

I tried to think of what I knew about mid-century poetry movements and the relationship between the Cambridge School and L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry.

My face stared back at me from the light-rimmed mirror. It was the face of someone realising they knew nothing about any poetry later than Des Imagistes.

My hairdresser snipped swiftly around my head. Hair fell asymmetrically around me.

Fragments, I said. Mr Prynne’s work is fragmented.

To either side of me were other people being snipped at. It was central Cambridge. No doubt they were all professors. Probably ninety percent of them had written books on the British Poetry Revival. One of them at least was clearly the world expert on Deleuze. They had all stopped reading Take a Break and were listening to me fail to know about poetry.

Fragmented? said my hairdresser.

Yes, I said. His work is fragmented, self-reflective and metaphorically asymmetric.

And your own poetry? prompted my hairdresser.

Isn’t, I said, and asked him about styling mousse.

I had the same conversation at three-month intervals until my hairdresser retired to a beach in Italy.

Since then, I have grown my hair long, and do my best to avoid discussing poetry.

PHOTOGRAPHY

TELEVISION

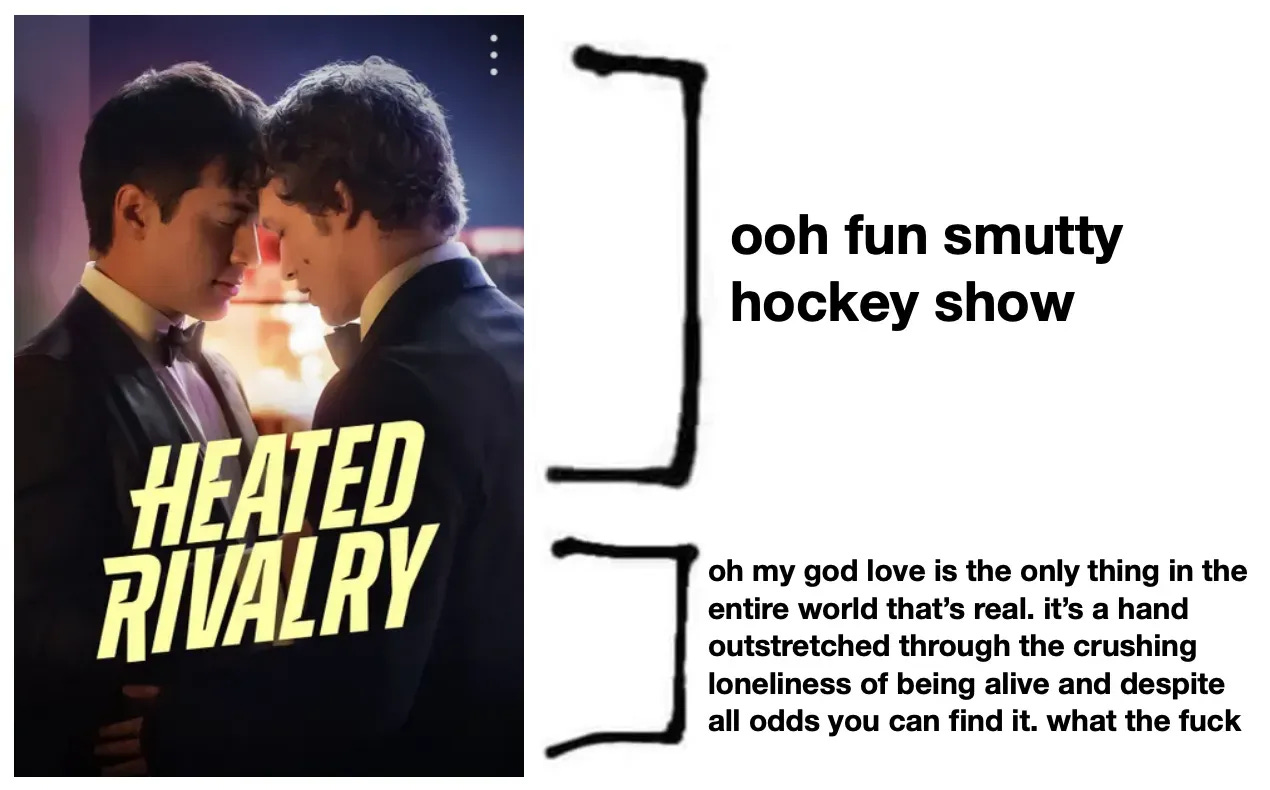

Hot hockey

Jenka Gurfinkel on Heated Rivalry as anti-dystopian art: a queer hockey romance offering pleasure, mutuality, and joy in a media landscape saturated with violence.

Heated Rivalry and the Art of Anti-Dystopia

—Jenka Gurfinkel in Jenka’s Substack

As I sit down to write this, the first episode of the show Heated Rivalry has been out in North America and Australia for less than 2 months. The 6th and final episode has been out only 3 weeks. In that time the show has amassed over 600 million minutes of streaming on HBO alone, increasing, in a “highly unusual” growth curve, 10x since its debut. The show has just premiered in the UK 3 days ago, and it is already a pirated hit worldwide, including in Russia and China, where it is not only unavailable but, due to its LGBTQ subject matter, banned.

The stunning, astronomical rise of Heated Rivalry has found us all trying to answer the question Vanity Fair poses: “Why can’t we stop talking about Heated Rivalry”? Why has this seemingly niche show with a modest budget and virtually no promotion, produced for Canadian streaming service Crave, with just 4 million subscribers, led by a cast of unknowns, about an autistic half-Asian and a traumatized Russian involved in a secret love affair, based on a queer hockey romance book series, taken over the world? How did this happen? Who is this pair of neophytes no one had heard of a month prior, suddenly presenting at the Golden Globes? WTF is going on?

Sure, it’s a faithful adaptation of a best-selling book series with a fan base already built in. Yes, it dutifully adheres to the conventions of the Romance genre, and romance will never let you down when it comes to a happy ending. It appeals to gay men and queer people for a myriad of reasons. It appeals to straight women, and women generally, for a myriad of reasons. It even appeals to straight men. (To paraphrase an Instagram reel that I saw floating by, “Hollander and Rozanov are your buddies. And you’re always happy for your buddies to get laid. And if they’re getting laid with each other, great!”) Obviously, the chemistry between the actors is unrivaled, and the standom they’ve inspired is at a boy-band fever pitch. The film-craft is absolutely superb, sending the last two episodes of the first season to #12 and #13 on IMDB’s list of top TV episodes of all time (again, the show hasn’t been out 2 months). On and on and on. There are many reasons to be enamored with this piece of visual storytelling media.

So I would like to add one more reason to the mix.

It’s because Heated Rivalry is Anti-Dystopia art.

The 21st-century entertainment landscape is filled with dystopian fantasies that inure people to violence, brutality, and trauma. In the parlance of our time, any one of these can be appended with the postfix “-porn” to efficiently communicate the ubiquity and banality of these kinds of explicit visuals within the culture. Dystopian movies and TV shows have transcended mere entertainment and become cultural shorthand. We refer to real-life events in the frame of reference of The Hunger Games or Squid Games or Mad Max or The Handmaid’s Tale. Reality has become Black Mirror. Dystopia’s vernacular of dehumanization, desensitization, and cruelty, especially towards women, seeps into everything. From comedy (the jarringly gratuitous gun violence ostensibly played for laughs in The Out-Laws), to fantasy (the pornographically lurid murder montage of one woman stabbing, choking, slicing the throat of another over and over in Wheel of Time)—to action (the glorified dissociation in Lioness), to drama (the grimy bleakness of Euphoria). Even superhero movies, which draw an obviously younger audience, expose viewers to hyper-real terrorism spectacles from the destruction of cities on par with 9/11 to the destruction of half of all life in the universe with the snap of a finger. Deeply disturbing and inhumane narratives and visuals in the guise of entertainment are constantly streaming into our eyeballs like we are all living in A Clockwork Orange. Dystopia as cultural shorthand strikes again.

Heated Rivalry might not be science fiction, but it, too, is a fantasy set in a speculative universe: in that universe, the captain of a major league hockey team publicly comes out, setting in motion a cascade of events that diverge from our current reality in which, out of thousands of players, there are currently zero openly gay or bi men actively competing in any of the major North American sports leagues.

As it ascends to the status of global phenomenon, creating an entire new cultural shorthand and lexicon along the way, Heated Rivalry offers a cinematic universe that references our own but casts an alternate vision of a world that’s possible—a world of pleasure, mutuality, humanness, intimacy, creativity, and joy.

Substackers featured in this edition

Art & Photography: Irfan Ajvazi, Art in Latin America, The Analog Post

Video & Audio: Cosmos

Writing: Adam Mastroianni, Andrew Truong, Harriet Truscott, Jenka Gurfinkel

Recently launched

Former Vanity Fair editor Radhika Jones has started a Substack, where she’ll be “writing about the books that are on my mind, on my nightstand, and popping up in the culture.” First up: Wuthering Heights, just in time for the Emerald Fennell adaptation coming out next month.

Fashion brand Veronica Beard has launched A Need to Know Basis, where the founders—both named Veronica—will be sharing “hacks, secrets, shortcuts, inspiration—to make our lives, and your lives—chicer and easier.”

Inspired by the writers and creators featured in the Weekender? Starting your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

Yet Substack is launching a TV platform...this is why the written word, on paper, is the only way to ultimately be free of algorithms and data harvesting.

In this age of AI, the ability to express ideas clearly and precisely has become a genuine advantage. Those who can communicate their thinking with sharpness and articulate their thoughts with clarity are far better equipped to engage with the world.

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”- Wittgenstein