“I want to be looked at and never forgotten, desired and never owned”

In this edition of the Weekender: desiring desire, recycled time, and the stories of J.D. Salinger

This week, we’re contemplating time, retranslating Shakespeare, desiring desire, and going live from a goat farm.

ART

In search of Joan Mitchell

Annie Fell opens her essay about Joan Mitchell with an anecdote about trying—and failing—to see the artist’s work in Paris.

The Magic Eye

—

inA couple years ago, I got the idea that I should spend a week in Paris by myself. Considering I have a boyfriend who could have gone with me and that, perhaps more pertinently, I don’t speak French, the decision was confusing to a handful of people I know. I was satisfied by my own reasoning for the trip—I wanted to travel alone, to be in a situation in which I’m entirely out of my element, at least once while I’m young. Also, JetBlue had a sale. Still, I could read the awkwardness in their eyes, the real questions not being asked, when they’d look at me and carefully go, “So … what are you going to do there?”

Really, what I wanted to do there was see the Joan Mitchell paintings at the Centre Pompidou. I’d still never seen a piece of hers in person then, the frenetic swipes and smears which I loved so much observed only ever through my various screens. A depressing thought! While it hadn’t been part of my decision to take the trip, in my loose planning it came to hold a kind of post hoc, kismet-like significance for me—a chance to finally commune with Mitchell, my fellow Chicagoan-turned-New-Yorker, in the country that she made her ultimate home.

Not long after touching down at Charles de Gaulle, I began to realize the extent of my hubris. As it turned out, being alone in a country where you can’t properly communicate with the majority of other people is an alienating—and, worse yet, often humiliating—experience. (This is something that most people could probably figure on their own, but like a lot of things, I had to find it out for myself the hard way.) With the first day of my trip thwarted by pathetic bouts of public weeping, I decided to scrap my plans and just go see the Mitchells.

In the museum at the Centre Pompidou, in a chafed and edgy mood, I scoured the Modern floor and found nothing. Then I did the same on the Contemporary floor, and also found nothing. Then I approached a gallery attendant and asked, in a kind of French that was probably no better than a dog’s, where the Joan Mitchells were. She screwed up her face.

“Comment?”

“Eugh…” I tried again, “Joan Mitchell?”

“Non.”

She was right. With yet more tears welling, I huddled into a corner and pulled up the museum’s website on my phone, and discovered then that not a single one of their Mitchells was on public view. I have done so many very stupid things in my life, and still, rarely have I ever felt like a bigger dumbass. Embarrassed, I took the seemingly interminable series of escalators back down to the gift shop where, at least, I found a postcard featuring “Chasse Interdite” (1973). For this, I would have to settle.

“Down and out in Paris”—this is how Mitchell described her move to the city, though her reasons for feeling as such were much better than my own. Her relocation from New York was spontaneous and, according to her, not completely by choice. She tells the story over 30 years after the fact, in Marion Cajori’s 1992 documentary Joan Mitchell: Portrait of an Abstract Painter. She’d found herself there at the whim of her boyfriend, Jean-Paul Riopelle, a French-Canadian painter and alcoholic, who also happened to be married to another woman. “I never wanted to move here,” she explains to Cajori. “I felt like an outsider … profoundly.”

Obviously it’s easy to feel like an outsider in a foreign country, even if you’re not there dating a philandering drunk. But the sentiment—regardless of whether she was living in Paris or New York or her native Chicago—is a recurring theme in her biography, maybe even the defining one.

The operative word, though, is “felt.” If you take a cursory look at her life, it’s inarguable that Mitchell was an insider.

PAINTING

HOROLOGY

Timepiece

Rhian Sasseen writes about her fascination with wristwatches, particularly those that have been passed down, appropriately, through time.

The return of phrase books

—

inWhat we understand to be time is a fantasy, a technology. A human invention both at odds and in cahoots with the chronology of our bodies and the natural world that surrounds us. Clock time exists as a linear progression: the seconds clot into the minutes that bleed into the hours, the amorphous fragrant hours, that constitute a life. Come spring, nature may regenerate, but humans lack this circularity, this hardy perennialism. We are not plants; from death, we do not grow back.

Nearly a year ago, I bought my first watch in a decade. Nothing fancy: a cheap Timex strung up on a black leather strap. As a teenager in the early 2000s invested in presenting an “eccentric” sensibility to the world, I used to wear a string of three or four of them to a wrist, more a fashion statement, a championing of the analog over the digital, than any real commitment towards keeping any kind of schedule. Flush with puberty, I was a walking compendium of time zones, my choice in attire an inadvertent throwback to the initial purpose of the watch, that of a lady’s piece of jewelry. (The intended gender of the wearer changed, writes the journalist Dan Falk in his book In Search of Time: The History, Physics, and Philosophy of Time, during World War I, when soldiers took to wearing wristwatches in the trenches.)

Some of these watches that I wore were gifts or hand-me-downs—when I was ten, an aunt passed on to me a silvery wristwatch with planets in place of numbers—but most of them came from the local flea markets or antique malls, of which there existed what seems to me now an unusually high number in my West Coast suburban town. When I moved my arm, these watches would clink against each other, tick tock tick tock, and the sound fascinated me, the rhythm of time moving forward without me doing anything to help it. It simply was. I’d think, in passing, about this recycled time, and the other girls, the women, who’d worn these watches before me, adorning themselves with the hours and the minutes, evidence of a life moved in accordance with a present long since in the past.

PHOTOGRAPHY

POETRY

Selected poems

—

inCAREER CHANGE

LITERATURE

Salinger, revisited

Combing through the work of J.D. Salinger, Henry Begler reconsiders The Catcher in the Rye—flawed, but better than its reputation—before spending time with the true standout of Salinger’s oeuvre: his short stories.

Slight Rebellion off Madison

—

inNine Stories is wonderful; it’s hard to imagine how it could be better. “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” “For Esmé—with Love and Squalor,” and “De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period”—these are just about as good as it gets, the others are very very good indeed, and only “Teddy,” which features a precocious child explaining the basics of Eastern philosophy before meeting an ambiguous fate, shades, in a slightly ominous foreshadowing of Salinger’s later preoccupations, into being a bit annoying. Most of these stories were originally published in The New Yorker, and reading them made me think of how I used to pick up my parents’ copy and come away from the fiction section slightly disgusted. This was what adults wanted to spend their time reading about? Mannered stories about boring upper-middle-class people where nothing even happens?

It’s still difficult to explain exactly what it is about these stories that makes them so good. In contrast to Catcher’s over-explanatory nature, they leave much unsaid, letting everything come out naturally through the masterful and realistic dialogue. Like Hemingway, Salinger was traumatized by war, and perhaps this accounts for their shared tactic of dealing with extremes of emotion through understatement and implication. But where Hemingway wrote of taciturn, stoic man’s men, Salinger mostly deals with quotidian, slightly bohemian upper-middle-class life. And of course, a lot of people went through extreme trauma in the war, and very few of them became the great writers of postwar America. Perhaps the appeal is better explained by the following anecdote.

There’s something that happens to me occasionally, maybe once a year if I’m lucky, when I finish a really really good novel. It’s a sort of fleeting Buddhistic awareness or minor spiritual awakening. I still remember the morning I finished Little, Big by John Crowley and walked out of my ugly, drab apartment on an ugly, drab Los Angeles street and suddenly saw the pomegranate tree outside my door in the true fullness of its being. I had walked by it probably hundreds of times and never really seen it. Salinger’s short stories, though they didn’t have this exact effect on me, are attempting to work their way through the same phenomenon. Almost all of them feature this sudden epiphany or shift in consciousness. This has of course become the standard way to write a short story in the last century; outside of genre fiction, there are very few Poes or O. Henrys out there writing stories with a standard plot moving from A to B. When I was younger I had a hard time recognizing epiphany’s validity as a literary device, which partially explains my earlier rejection of the New Yorker style (of course, a lot of them are simply bad). But reading these stories, which seem to have been transmitted from some reality just a little more heightened, strange, and mystical, a little bit more aware of the world stripped of the blinkers of everyday consciousness, helped me understand how it is that one of the functions of literature, if not the function, can be as a tool that briefly shocks one into that sort of awareness. At least for people like me, who are too dumb or impatient to read European philosophy or contemplate the classic spiritual texts.

ART

Phenakistoscope, 1833, shared by Meredith Lewis

DESIRE

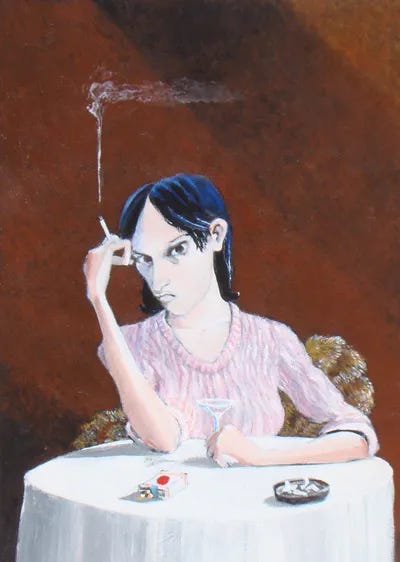

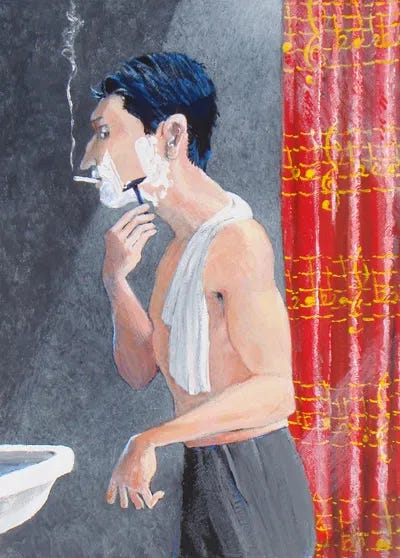

On beauty

Earlier this week, Substack partnered with Camille Sojit Pecha to host A Night of Desire, a series of readings at the iconic Wall Street Bath & Spa. Sherry Ning’s reading took a meta approach to the night’s topic: her essay about beauty is, at its heart, about the desire to be desired.

I Want to Be Beautiful

—

inI want to be beautiful—the kind that lives forever in mythologies and novels and wet dreams behind closed eyes, like perfume soaked into the fibers of clothing days later. The kind that makes poets and artists shed big, opalescent tears.

I don’t want to be cute. I don’t want to be sweet. I want to be beautiful and I want beauty that tilts the world in my favor, making people ache without them knowing why. I want beauty that’s electrifying, the kind that makes you feel like you’re being burned alive all along your nerves.

I want to be the face in the frame, the figure stretched across a canvas in the languid posture of a spoiled cat who has never needed to chase anything because everything comes to her in time.

I want the perfect body, not for function but for worship. I’m not just moisturizing, I’m conducting a seance to resurrect my glow. 10 hours of sleep, Pilates, and beef bone broth—my routine is a shrine to transformations, a cocoon for the butterfly. Moony eyes muddied with brown mascara, thin white shirts that blur the shape of breasts, mismatched studs on the fat lobes of ears, lipstick-stained teeth like pinkish poker chips, I want to be messy and still be adored.

I want to be art. I don’t want to age. I want to be looked at and never forgotten, desired and never owned. I want to be a painting, something eaten by the eyes.

FOOD

Goatstack

We would be remiss if we didn’t remind readers that Grubstack, Substack’s live food fest, continues today, with events featuring Yotam Ottolenghi, David Lebovitz, Ruth Reichl, José Andrés, and more of the biggest names in food. Check out the schedule, and be sure to subscribe to get notified when they go live.

Here’s a snippet of one Grubstack conversation between regenerative farmers Finn Harries and Julius Roberts. Watch the full episode to see their discussion on farm-to-table cooking and to enjoy some very special guests: Julius’s goats.

Fresh from the Field

—

and in andTECHNO-OPTIMISM

Substackers featured in this edition

Art & Photography:

, , , ,Video & Audio:

, ,Writing:

, , , , ,Recently launched

Inspired by the writers featured in the Weekender? Creating your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

Easy to get lost in and just dream.

Making me ponder, what are the recurring themes in my biography and what will be the defining one? Worth pondering, possibly even rumination. Thank you. [post pertains to artist, Joan Mitchell]